Jason Schneider

the Camera Collector

Vintage Cameras for Film Fanatics:

Great Camera Picks and Buying Tips Aimed at Ardent Analog Addicts

By Jason Schneider

Shooting with a vintage film camera in 2024 can feel somewhat akin to cruising down Main Street in your 1934 Hupmobile Eight, especially if the mechanical marvel you’re toting looks nothing like a modern DSLR, mirrorless, or point-and-shoot camera. Sometimes people just stare quizzically at the ancient camera hanging around my neck, but a surprising number come right up and ask, “What kind of camera is that?” or, more succinctly and less politely, “What the hell is that?” It always gives me a perverse satisfaction to reply sweetly, “Oh, that’s a 1955 Rolleiflex MX EVS,” or “It’s a 1961 Bronica S and the body is made entirely of stainless steel,” knowing full well that most people don’t have the blindest idea what I’m talking about. On the other hand, shooting with antique cameras has sparked many delightful conversations with knowledgeable photographers, and has also allowed me to shoot hundreds of impromptu portraits of perfect strangers—because people are usually more willing to have their pictures taken once you tell them you’re immortalizing them with a vintage camera and shooting on film,

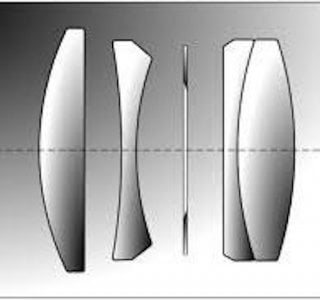

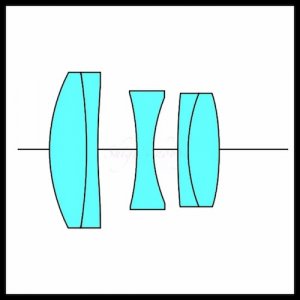

The iconic 4-element, 3-group Zeiss Tessar of 1902 is a vintage classic that has has been used by virtually every lens maker worldwide.

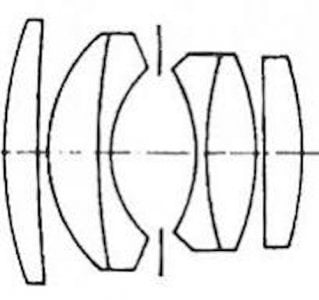

The nearly symmetrical 6-element, 4-group "Double Gauss" design was widely used for fast lenses. This is Berek's 50mm f/2 Leitz Summar.

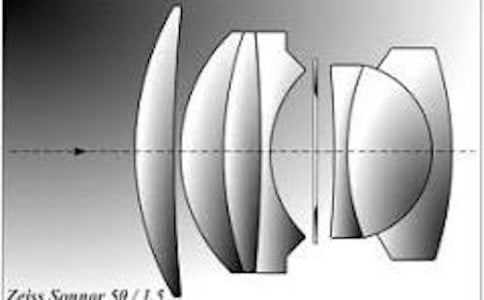

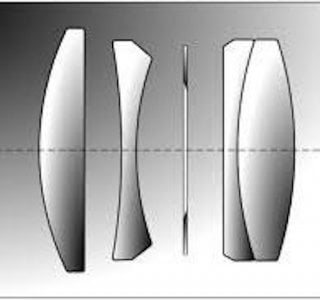

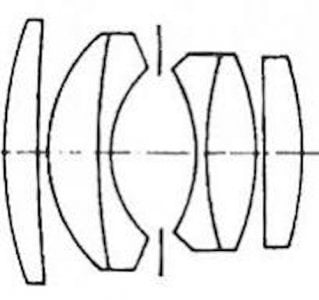

One of the main reasons many creative photographers opt for vintage film cameras is that they can capture images with that coveted “vintage look,” provided they’re used with original vintage lenses. These lenses are generally classical optical designs comprised of spherical section elements and they’re either single coated or uncoated. Examples: modified complex triplet designs based on the 50mm f/2 or f/1.5 Zeiss Sonnar, symmetrical or nearly symmetrical designs based on the Zeiss Planar (e.g. the Leitz Summar) or Zeiss Biotar, 5-element 3-group lenses based on the Voigtlander Heliar (e.g. the 75mm and 80mm f/3.5 and f/2.8 Zeiss Planars and Schneider Xenotars on late model Roilleflexes), and a plethora of lenses from virtually every lens company on earth based on the iconic 4-element, 3-grpup Zeiss Tessar, a design introduced 1902. All these lenses, and other vintage designs, can provide a “smooth, rounded” rendition of 3-dimensional objects, excellent central sharpness and detail, and somewhat lower contrast than current lenses. Many deliver gorgeous bokeh at their widest apertures and a distinctive “glow” in out-of-focus highlights that art photographers find especially attractive. In short, vintage lenses typically have optical “defects” that may adversely affect their measurable performance parameters (MTF and line pairs per millimeter resolution) but give them a charming and distinctive “personality” that is often (though not always) lacking in the latest contemporary lenses, many of which incorporate aspheric elements and surfaces.

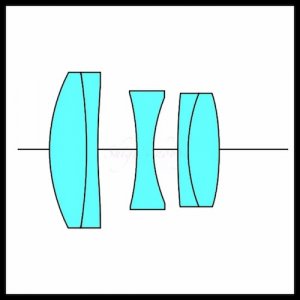

The 5-element, 3-group Voigtlander Heliar design inspired the Zeiss Planar and Schneider Xenotar lenses used on late model Rolleflexes.

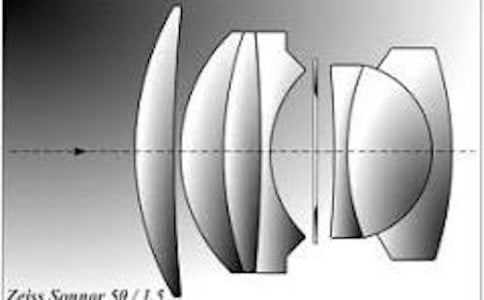

The 50mm f/1.5 Zeiss Sonnar. Ludwig Bertele's classic 7-element, 3 group design inspired the 50mm f/1.4 Nikkor-S.C and many other lenses.

What type of vintage camera is best for you?

What type or types of vintage camera works best for you depends entirely on what kind of subjects you typically shoot, your shooting style, and your personal preferences. There are no hard and fast rules, and virtually any camera can be pressed into service if you’re prepared to operate within its limitations and optimize all the variables. Case in point; Ansel Adams is renowned for his majestic landscapes, mostly shot with large format view cameras. However, his first camera was a Kodak Box Brownie No.1, and he used a huge variety of cameras, including a Zeiss Ikonta B, a Hasselblad 500 C/M, various Polaroids, and a plethora of different 35mm rangefinder cameras and SLRs over the course of his career. Adams was able to take great pictures, mostly in his signature style, no matter what kind of camera he used because he was a great photographer and knew how to get the best out of whatever camera he was shooting with. Bearing that in mind let’s look at the assets and limitations of the most common types of vintage cameras.

Note: None of the camera selections in each category is intended to be exhaustive or complete, so if your favorite model is among the missing, my apologies— it’s probably because I’ve never had any hands-on experience with it, not because I think it’s unworthy.

The Leica M3 of 1954, shown here with collapsible 50mm f/2 Summicron lens, ushered in the era of the modern multi-frame rangefinder 35.

35mm rangefinder cameras

Advantages:

More compact, lighter in weight, and quieter than most 35mm SLRs thanks to the absence of a mirror box and its flipping reflex mirror, rangefinder 35s can capture sharp images at slower handheld shutter speeds, and excel at street photography, grab shots, and other applications when discretion is required to capture unposed pictures of people. Their separate inverse Newtonian optical viewfinders provide a direct view of the subject that is equally bright regardless of the lens in use, a plus in low light shooting, and their ergonomic form factor and balance enhance their handling. Their built-in coupled rangefinders provide positive focus confirmation and faster manual focusing than their SLR counterparts, and because their focusing accuracy is independent of the focal length or aperture of the lens, they provide superior focusing accuracy with wide-angle and ultra-wide-angle lenses. Rangefinder 35s are great walkaround cameras and those with interchangeable lenses provide an extended range of shooting opportunities thanks to their enhanced optical flexibility.

The Nikon SP of 1957 to 1960 was the apotheosis of the Nikon rangefinder 35. It's a collector's prize but also a great vintage shooter!

Deficits:

Virtually all the disadvantages of 35mm rangefinder cameras can be attributed their inability to provide parallax-free, through-the-lens viewing like an SLR. As a result, vintage models (except for later Leica Ms) can’t focus closer than about 3 feet with the normal lens, and all are afflicted with parallax error that gets worse as you focus closer. Elite late model interchangeable lens rangefinder cameras like the Leica M3, M2, M4, etc., the Nikon SP and S3, and the Canon VI- and 7-series, provide multiple moving parallax-compensating frame lines in the finder that cover lenses of 3 to 6 different focal lengths as you focus, but none of them delivers the seamless flexibility of an SLR that automatically provides nearly perfect viewing accuracy with any lens, from fish-eye to super-tele. More traditional models lacking viewfinder frame lines, including screw-mount Leicas, and Contax rangefinder 35s from 1932 to 1961, require separate shoe-mount finders with manual parallax adjusters to accomplish the same thing, albeit a lot less conveniently. As ingenious as they are, rangefinder 35s with built-in parallax compensating frame lines are practical over a limited focal length range of perhaps 28-105mm; anything much longer and the frame is too small; anything much wider and a separate optical viewfinder is a better alternative. It’s also worth noting that no multi-frame range/viewfinder system or accessory viewfinder compensates for field frame size, the narrowing of the coverage angle of the lens as you focus closer. Both the Konica IIIA and IIIM of 1958 have a 1:1 viewfinder with frame lines that correct for parallax and field frame size, but neither one has interchangeable lenses. Both V- and VI-series Canons have an ingenious pin in the accessory shoe that rises to tilt mounted accessory viewfinders to compensate for parallax but this does not provide correction for field frame size. Finally, it's also worth noting that (excepti for screw-mount Leicas and Canons, which are fully compatible) interchangeable lens rangefinder cameras (including the Voigtlander Prominent, Aires V, Leica M, Nikon S-series and classic rangefinder Contax, all have unique mounts, which limits your choice of lenses and tends to make them more expensive. An interesting exception: Wide-angle Contax and Nikon rangefinder lenses work on either camera, but don’t try it with your nifty 50!

Canon VI-L of 1958 has reflected parallax-compensating frame lines for 50mm and 100mm lenses. Some claim it was the best of the breed.

Bottom line: if you’re determined to shoot with a vintage 35 and plan to include a lot of frame-filling head shots, frequently use telephotos longer than 90-100mm, or favor ultra-wide-angle lenses for capturing scenic vistas, do yourself a favor and acquire a classic 35mm SLR instead of, or in addition to, a rangefinder 35. You’ll be glad you did.

The Cintax IIa, which debuted in 1950, was the last meter-less Contax. It's a masterpiece of elegant design, and a superb picture taker.

Recommended rangefinder 35s

M-series Leicas are superb cameras, but bodies and M-mount lenses are costly, and earlier M-series bodies often require expensive service. Ditto for the Nikon SP and S3 which are now around 70 years old, but you can generally snag a clean mid-50s Nikon S2 (which has only one stationary 50mm frame line) for $350-$550 with 50mm f/1.4 Nikkor-S.C, and its minimalist elegance makes it my personal favorite. The most practical and affordable choice in an elite vintage rangefinder 35 is a Canon. The trigger wind Canon VT/VT DeLuxe, lever wind VL and L1, and the later VI-T and VI-L (with reflected finder frame lines) are all excellent cameras as are the last of the breed, the Canon P, Canon 7s, and the (pricier) 7sZ, the final model in the series. The Contax IIa and IIIa ($250 to $350 with 50mm f/2 or f/1.5 Sonnar) are gorgeous cameras that are more reliable and easier to fix than their prewar counterparts, the Contax II and III, but they’re still costly to repair and lenses other than 50mm Sonnars are expensive. Earlier Leicas and Canons such as the Leica IIIa and IIIc, and Canon IVSb and IVSB2 are fine and serviceable cameras available at moderate prices and capable of first class results but you must figure in the cost of a CLA in your price calculations as these vintage classics are getting long in the tooth.

Konica IIIA of 1958 has a magnificent 1:1 range/viewfinder with projected frame lines that correct for field frame size as well as parallax error.

Other fine performing, affordable vintage rangefinder 35s without interchangeable lenses: The folding Kodak Retina IIa with 50mm f/2 Schneider Xenon or Rodenstock Heligon lens, which folds flatter than the later Retina IIIc and IIIC (Big C), which are also excellent shooters with larger, clearer viewfinders, especially the IIIC. The previously mentioned Konica IIIA with superb parallax correcting 1:1 viewfinder and 48mm f/2 or 50mmm /1.8 Hexanon lens, the Canon Canonet QL17 GIII G3 with 40mm f/1.7 Canon, and the Yashica ELECTRO 35 GTN with 45mm f/1.7 Color-Yashinion DX lens are all readily available at attractive prices.

The Kodak Retina IIa of the early '50s offered a rangefinder focusing 50mm f/2 lens and a slimmer, handier form factor than later Retinas. Nice!

35mm SLRs

Background

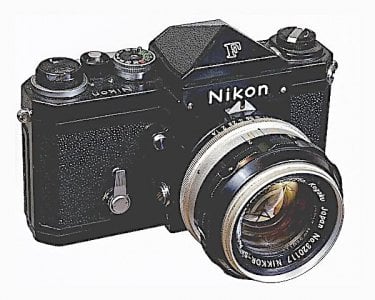

With the introduction of the landmark Nikon F, the first truly professional system 35mm SLR, in 1959, the 35mm SLR began to eclipse the interchangeable lens rangefinder 35 as the dominant camera type used by pros and serious photo enthusiasts. Even among the elite “Big 4,” Leica, Nikon, Canon, and Contax, only the Leica M survives today in both analog and digital form. The Zeiss Contax IIa and IIIa bit the dust by 1961, the rangefinder Nikons were effectively phased out (except for later commemorative limited editions) with the demise of the Nikon S3 in 1964, and Canon soldiered on until the final Canon 7sZ rolled off the production line in September 1968. By the mid ‘60s the 35 mm SLR was king and cameras such as the brood-spectrum Pentax Spotmatic, Minolta SR-T 101, Canon FP and FT, and the pro caliber Nikon F, Canon F1, and Topcon Super D sold in much larger numbers than even the top-selling rangefinder 35s during the analog era.

.

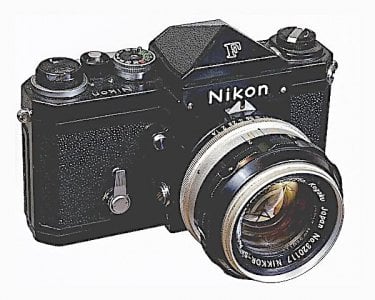

Nikon F: Shown here in black with plain pentaprism, 50mm f/1.4 Nikkor, it was the camera that ushered in the era of 35mm SLR dominance.

Great Camera Picks and Buying Tips Aimed at Ardent Analog Addicts

By Jason Schneider

Shooting with a vintage film camera in 2024 can feel somewhat akin to cruising down Main Street in your 1934 Hupmobile Eight, especially if the mechanical marvel you’re toting looks nothing like a modern DSLR, mirrorless, or point-and-shoot camera. Sometimes people just stare quizzically at the ancient camera hanging around my neck, but a surprising number come right up and ask, “What kind of camera is that?” or, more succinctly and less politely, “What the hell is that?” It always gives me a perverse satisfaction to reply sweetly, “Oh, that’s a 1955 Rolleiflex MX EVS,” or “It’s a 1961 Bronica S and the body is made entirely of stainless steel,” knowing full well that most people don’t have the blindest idea what I’m talking about. On the other hand, shooting with antique cameras has sparked many delightful conversations with knowledgeable photographers, and has also allowed me to shoot hundreds of impromptu portraits of perfect strangers—because people are usually more willing to have their pictures taken once you tell them you’re immortalizing them with a vintage camera and shooting on film,

The iconic 4-element, 3-group Zeiss Tessar of 1902 is a vintage classic that has has been used by virtually every lens maker worldwide.

The nearly symmetrical 6-element, 4-group "Double Gauss" design was widely used for fast lenses. This is Berek's 50mm f/2 Leitz Summar.

One of the main reasons many creative photographers opt for vintage film cameras is that they can capture images with that coveted “vintage look,” provided they’re used with original vintage lenses. These lenses are generally classical optical designs comprised of spherical section elements and they’re either single coated or uncoated. Examples: modified complex triplet designs based on the 50mm f/2 or f/1.5 Zeiss Sonnar, symmetrical or nearly symmetrical designs based on the Zeiss Planar (e.g. the Leitz Summar) or Zeiss Biotar, 5-element 3-group lenses based on the Voigtlander Heliar (e.g. the 75mm and 80mm f/3.5 and f/2.8 Zeiss Planars and Schneider Xenotars on late model Roilleflexes), and a plethora of lenses from virtually every lens company on earth based on the iconic 4-element, 3-grpup Zeiss Tessar, a design introduced 1902. All these lenses, and other vintage designs, can provide a “smooth, rounded” rendition of 3-dimensional objects, excellent central sharpness and detail, and somewhat lower contrast than current lenses. Many deliver gorgeous bokeh at their widest apertures and a distinctive “glow” in out-of-focus highlights that art photographers find especially attractive. In short, vintage lenses typically have optical “defects” that may adversely affect their measurable performance parameters (MTF and line pairs per millimeter resolution) but give them a charming and distinctive “personality” that is often (though not always) lacking in the latest contemporary lenses, many of which incorporate aspheric elements and surfaces.

The 5-element, 3-group Voigtlander Heliar design inspired the Zeiss Planar and Schneider Xenotar lenses used on late model Rolleflexes.

The 50mm f/1.5 Zeiss Sonnar. Ludwig Bertele's classic 7-element, 3 group design inspired the 50mm f/1.4 Nikkor-S.C and many other lenses.

What type of vintage camera is best for you?

What type or types of vintage camera works best for you depends entirely on what kind of subjects you typically shoot, your shooting style, and your personal preferences. There are no hard and fast rules, and virtually any camera can be pressed into service if you’re prepared to operate within its limitations and optimize all the variables. Case in point; Ansel Adams is renowned for his majestic landscapes, mostly shot with large format view cameras. However, his first camera was a Kodak Box Brownie No.1, and he used a huge variety of cameras, including a Zeiss Ikonta B, a Hasselblad 500 C/M, various Polaroids, and a plethora of different 35mm rangefinder cameras and SLRs over the course of his career. Adams was able to take great pictures, mostly in his signature style, no matter what kind of camera he used because he was a great photographer and knew how to get the best out of whatever camera he was shooting with. Bearing that in mind let’s look at the assets and limitations of the most common types of vintage cameras.

Note: None of the camera selections in each category is intended to be exhaustive or complete, so if your favorite model is among the missing, my apologies— it’s probably because I’ve never had any hands-on experience with it, not because I think it’s unworthy.

The Leica M3 of 1954, shown here with collapsible 50mm f/2 Summicron lens, ushered in the era of the modern multi-frame rangefinder 35.

35mm rangefinder cameras

Advantages:

More compact, lighter in weight, and quieter than most 35mm SLRs thanks to the absence of a mirror box and its flipping reflex mirror, rangefinder 35s can capture sharp images at slower handheld shutter speeds, and excel at street photography, grab shots, and other applications when discretion is required to capture unposed pictures of people. Their separate inverse Newtonian optical viewfinders provide a direct view of the subject that is equally bright regardless of the lens in use, a plus in low light shooting, and their ergonomic form factor and balance enhance their handling. Their built-in coupled rangefinders provide positive focus confirmation and faster manual focusing than their SLR counterparts, and because their focusing accuracy is independent of the focal length or aperture of the lens, they provide superior focusing accuracy with wide-angle and ultra-wide-angle lenses. Rangefinder 35s are great walkaround cameras and those with interchangeable lenses provide an extended range of shooting opportunities thanks to their enhanced optical flexibility.

The Nikon SP of 1957 to 1960 was the apotheosis of the Nikon rangefinder 35. It's a collector's prize but also a great vintage shooter!

Deficits:

Virtually all the disadvantages of 35mm rangefinder cameras can be attributed their inability to provide parallax-free, through-the-lens viewing like an SLR. As a result, vintage models (except for later Leica Ms) can’t focus closer than about 3 feet with the normal lens, and all are afflicted with parallax error that gets worse as you focus closer. Elite late model interchangeable lens rangefinder cameras like the Leica M3, M2, M4, etc., the Nikon SP and S3, and the Canon VI- and 7-series, provide multiple moving parallax-compensating frame lines in the finder that cover lenses of 3 to 6 different focal lengths as you focus, but none of them delivers the seamless flexibility of an SLR that automatically provides nearly perfect viewing accuracy with any lens, from fish-eye to super-tele. More traditional models lacking viewfinder frame lines, including screw-mount Leicas, and Contax rangefinder 35s from 1932 to 1961, require separate shoe-mount finders with manual parallax adjusters to accomplish the same thing, albeit a lot less conveniently. As ingenious as they are, rangefinder 35s with built-in parallax compensating frame lines are practical over a limited focal length range of perhaps 28-105mm; anything much longer and the frame is too small; anything much wider and a separate optical viewfinder is a better alternative. It’s also worth noting that no multi-frame range/viewfinder system or accessory viewfinder compensates for field frame size, the narrowing of the coverage angle of the lens as you focus closer. Both the Konica IIIA and IIIM of 1958 have a 1:1 viewfinder with frame lines that correct for parallax and field frame size, but neither one has interchangeable lenses. Both V- and VI-series Canons have an ingenious pin in the accessory shoe that rises to tilt mounted accessory viewfinders to compensate for parallax but this does not provide correction for field frame size. Finally, it's also worth noting that (excepti for screw-mount Leicas and Canons, which are fully compatible) interchangeable lens rangefinder cameras (including the Voigtlander Prominent, Aires V, Leica M, Nikon S-series and classic rangefinder Contax, all have unique mounts, which limits your choice of lenses and tends to make them more expensive. An interesting exception: Wide-angle Contax and Nikon rangefinder lenses work on either camera, but don’t try it with your nifty 50!

Canon VI-L of 1958 has reflected parallax-compensating frame lines for 50mm and 100mm lenses. Some claim it was the best of the breed.

Bottom line: if you’re determined to shoot with a vintage 35 and plan to include a lot of frame-filling head shots, frequently use telephotos longer than 90-100mm, or favor ultra-wide-angle lenses for capturing scenic vistas, do yourself a favor and acquire a classic 35mm SLR instead of, or in addition to, a rangefinder 35. You’ll be glad you did.

The Cintax IIa, which debuted in 1950, was the last meter-less Contax. It's a masterpiece of elegant design, and a superb picture taker.

Recommended rangefinder 35s

M-series Leicas are superb cameras, but bodies and M-mount lenses are costly, and earlier M-series bodies often require expensive service. Ditto for the Nikon SP and S3 which are now around 70 years old, but you can generally snag a clean mid-50s Nikon S2 (which has only one stationary 50mm frame line) for $350-$550 with 50mm f/1.4 Nikkor-S.C, and its minimalist elegance makes it my personal favorite. The most practical and affordable choice in an elite vintage rangefinder 35 is a Canon. The trigger wind Canon VT/VT DeLuxe, lever wind VL and L1, and the later VI-T and VI-L (with reflected finder frame lines) are all excellent cameras as are the last of the breed, the Canon P, Canon 7s, and the (pricier) 7sZ, the final model in the series. The Contax IIa and IIIa ($250 to $350 with 50mm f/2 or f/1.5 Sonnar) are gorgeous cameras that are more reliable and easier to fix than their prewar counterparts, the Contax II and III, but they’re still costly to repair and lenses other than 50mm Sonnars are expensive. Earlier Leicas and Canons such as the Leica IIIa and IIIc, and Canon IVSb and IVSB2 are fine and serviceable cameras available at moderate prices and capable of first class results but you must figure in the cost of a CLA in your price calculations as these vintage classics are getting long in the tooth.

Konica IIIA of 1958 has a magnificent 1:1 range/viewfinder with projected frame lines that correct for field frame size as well as parallax error.

Other fine performing, affordable vintage rangefinder 35s without interchangeable lenses: The folding Kodak Retina IIa with 50mm f/2 Schneider Xenon or Rodenstock Heligon lens, which folds flatter than the later Retina IIIc and IIIC (Big C), which are also excellent shooters with larger, clearer viewfinders, especially the IIIC. The previously mentioned Konica IIIA with superb parallax correcting 1:1 viewfinder and 48mm f/2 or 50mmm /1.8 Hexanon lens, the Canon Canonet QL17 GIII G3 with 40mm f/1.7 Canon, and the Yashica ELECTRO 35 GTN with 45mm f/1.7 Color-Yashinion DX lens are all readily available at attractive prices.

The Kodak Retina IIa of the early '50s offered a rangefinder focusing 50mm f/2 lens and a slimmer, handier form factor than later Retinas. Nice!

35mm SLRs

Background

With the introduction of the landmark Nikon F, the first truly professional system 35mm SLR, in 1959, the 35mm SLR began to eclipse the interchangeable lens rangefinder 35 as the dominant camera type used by pros and serious photo enthusiasts. Even among the elite “Big 4,” Leica, Nikon, Canon, and Contax, only the Leica M survives today in both analog and digital form. The Zeiss Contax IIa and IIIa bit the dust by 1961, the rangefinder Nikons were effectively phased out (except for later commemorative limited editions) with the demise of the Nikon S3 in 1964, and Canon soldiered on until the final Canon 7sZ rolled off the production line in September 1968. By the mid ‘60s the 35 mm SLR was king and cameras such as the brood-spectrum Pentax Spotmatic, Minolta SR-T 101, Canon FP and FT, and the pro caliber Nikon F, Canon F1, and Topcon Super D sold in much larger numbers than even the top-selling rangefinder 35s during the analog era.

.

Nikon F: Shown here in black with plain pentaprism, 50mm f/1.4 Nikkor, it was the camera that ushered in the era of 35mm SLR dominance.

Last edited:

Jason Schneider

the Camera Collector

The main reason for the phenomenal success of the SLR was its ability to provide a high-magnification parallax-free viewing image with virtually any lens that could be mounted on the camera. Using a 45°-angled reflex mirror positioned behind the lens to reflect the image formed by the lens into the viewfinder, the real image on the finder screen could also be focused directly without requiring any coupling arms or cams, just like the lens on a view camera can be focused on a ground-glass screen. Some early 35mm SLRs like the Russian Sport, and the German Exakta I (1936) and II (1949) used waist-level finders, resulting in a right-side-up, but laterally reversed viewing image. But, in the Italian Rectaflex of 1948 and the East German Zeiss Ikon Contax S of 1949 a solid glass pentaprism was mounted atop the focusing screen to provide a right-side-up, laterally correct viewing image, a feature soon adopted by all the leading Japanese camera manufacturers including Pentax, Yashica, Canon, et al. Since the SLR’s reflex mirror must move out of the light path prior to the shutter firing, the viewfinder image on some SLRs (e.g. most Exaktas, the Praktiflex, Hasselblad 500C, Pentacon 6 and Bronica S) blacks out the instant you press the shutter release and returns only when the film is wound to the next exposure and/or the shutter is cocked. To eliminate this “psychological” disadvantage, all modern 35mm SLRs have instant-return mirrors, a feature pioneered on the Asahiflex IIB of 1954. The sole exceptions: the Canon Pellix and Canon EOS RT both of which have fixed semi-transparent pellicle mirrors that reduce light transmission to the film by about ½ stop, and, in the case if the Pellix, adversely affect image quality.

Nikon F2 of 1971 to 1980 is reputed to be the best 35mm SLR Nikon ever made. It's shown here with DP-1 prism and 50mm f/1.4 Nikkor.

Advantages

]The big advantage of any SLR is its ability to provide parallax-free viewing with virtually any lens that can be mounted in the camera, and at any focusing distance down to, and including, the macro range. This advantage is optimized in 35mm SLRs, which will accommodate lenses ranging from fisheyes to super-telephotos. Some pro-grade 35mm SLRs, notably the Nikon F and F2, original Canon F-1, and Minolta XK have viewfinders that show 100% of the on-film image, but most show about 97% which is close enough for most applications. Most 35mm SLRs (e.g. the Nikon F) provide a viewfinder magnification of about 0.8x (80% of life-size) with the 50mm normal lens. That’s why some 35mm SLRs from major makers, notably Exakta, Nikon, Minolta, and Topcon fitted their cameras with 58mm lenses to achieve a life-size (1:1) viewing image, and Olympus configured their OM-series viewfinders to achieve a 0.92x magnification with a coverage of 97%. Optical flexibility is the SLR’s sine qua non and is largely responsible for the 35mm SLR’s dominance from the mid ‘60s until the dawn of the digital era around 2002.

Canton F-1 NEW, the final and most advanced iteration of the F-1, debuted in 1981. it features a titanium shutter with speeds to 1/2000 sec.

Disadvantages

The major downsides of 35mm SLRs are all direct results of the moving mirror required for through-the-lens viewing and the relatively bulky mechanical assembly comprising the mirror box. Since the mirror must move out if the light path before the shutter fires its movement causes some degree of camera shake that affects the exposure and cannot be eliminated entirely even with ingenious braking systems, etc. Fortunately, the action of the returning mirror takes place after the shutter fires, so it has no effect on the captured image. Result: shooting handheld at slow shutter speeds with a 35mm SLR is more likely to result in unsharp pictures, especially when shooting at 1/30 sec and slower. Also, the combined sound of an SLR’s shutter and mirror is usually noticeably louder that the discreet click of a typical rangefinder camera, and SLRs are usually larger and heavier than comparable rangefinder cameras due to the extra size and weight of the mirror box and pentaprism. Indeed, it was the quest for smaller sized SLRs that resulted in the “compact SLR revolution” of the ‘70s that yielded such diminutive classics as the Olympus OM series and the Pentax ME and MX. Finally, SLRs generally have a longer shutter release time lag—the interval between pressing the shutter release and executing the exposure—than cameras without reflex mirrors. Many of the factors noted above also explain why mirrorless cameras have largely supplanted DSLRs in the current digital era.

Toopcon Super D (marketed in the U.S. by Beseler) had one if the first TTL metering systems. Lens is the superb 58mm f/1.4 R.E. Auto-Topcor.

Recommended 35mm SLRs

There are literally scores of worthy 35mm SLRs currently available on the used market and it’s impossible to list them all here. However, here is a selection of my personal favorites, all of which have been vetted with experienced camera repair people and longtime camera experts. For the convenience of vintage analog shooters, they’re arranged in 3 broad categories, pro-aimed, enthusiast or intermediate level, and broad spectrum of mass market. Note: Just because a camera is listed in one group doesn’t mean its use is confined to that category, a notable example being the “Intermediate” Nikon FM2, which was the mainstay of countless pros.

Canon T90 of 1986, the top of T-series line, is a unique multi-mode FD-mount SLR with a built-in 4.5 fps motor. It's a great vintage shooter.

Pro-level 35mm SLRs

The following are all superbly constructed, super-rugged, full featured system cameras with extensive lines of first-rate optics that were marketed as professional cameras and/or used by many pros. The Nikon F (all iterations, now available at surprisingly modest prices), the Nikon F2 (widely regarded as Nikon’s best 35mm SLR ever), the Canon F-1 and the mildly upgraded F-1n, both extremely robust and reliable, the Canon New F-1, Canon’s top-of-the-line model from 1981 to 1992, and the Canon T90 of 1986 a unique multi-mode FD-mount SLR with built-in 4.5 fps motor drive, three metering systems, eight auto-exposure modes and two manual exposure modes for maximum versatility. The Topcon RE Super of 1963, marketed as a pro camera and used by the U.S. Navy, features an ingenious CdS-cell metering system behind slits in the reflex mirror, which reduces finder brightness somewhat, and its body as not quite as tanklike as a Nikon F2 or Canon F-1, but its line of Topcor lenses equals or surpasses that of its competitors. Some experts believe that the Leica R6.2 merits inclusion in this category due to its excellent (and expensive!) lens line and its straightforward design and robust reliability, which appealed to pros. Other late models worth looking into: Canon EOS 1-V, and the late lamented top-of-the line Nikon F6.

Intermediate level 35mm SLRs

The following cameras are in widespread use by serious photographers and some pros, have stood the test of time, and are often available at very moderate prices: Pentax Spotmatic, and the compact K-mount MX, Minolta SR-T 102/303, Nikon FM, FM2, FM3a (limited production, coveted, and expensive) and FE, Canon FTb, EF, and A1, Olympus OM-1, OM-1n OM-2n, Yashica FX-103 Program, Minolta X700, the Nikkormat FTn, and the Nikon F3/F3HP a pro/enthusiast crossover.

Budget-priced, mass market 35mm SLRs

Pentax K1000 (the archetypical student SLR), Canon AE-1 (over 5 million sold!), Canon TLb, Nikon EM, Konica Autoreflex TC, Chinon CP-7m, Olympus OMG. There are countless others available used at bargain prices.

Medium format SLRs (6x4.5, 6x6 and 6x7cm)

The main reason to choose a medium format SLR boils down to a single two-word phrase: image quality. If you’re determined to capture images for the ages on film, often make enlargements of 16 x 20 inches and larger, are prepared to tote a heavier, slower operating camera, pay more for a clean functional body (and considerably more for extra lenses) and shell out more for film, processing, and hi-res scanning, maybe a medium format SLR is the camera for you. These are great cameras, but they require a slower, more deliberate approach if you expect to get the most out of them. All take readily available 120 roll film, and (depending on the format) provide 16, 12, or 10 exposures per roll. Most have interchangeable film backs, a good thing since loading roll film is hardly the last word in speed or convenience. All have interchangeable lenses and detachable finders, and most have user-interchangeable finder screens.

Advantages

All medium format SLRs provide parallax-free viewing and though-the-lens focusing with all compatible lenses, and most show close to 100% of the on-film image, laterally reversed, when using a waist-level finder; often somewhat less than 100% if you mount a pentaprism finder. Many focal plane shutter models provide close focusing down to 0.5 or so with the normal lens, but others (e.g. the Hasselblad 500C and C/M) have a leaf shutter in each lens and minimum focus distance of 0.9m (3 ft.) with the normal lens. The latter require close-up lenses or accessories to get closer. All medium format SLRs provide automatic film stop and frame counting once you manually position the film before winding to the first exposure, but on some models it’s possible to get a blank exposure if the film back is out of sync with the shutter cocking mechanism in the body. In general, medium format SLRs have good handing and ergonomics, but they’re a lot larger and heavier than all but the heftiest pro 35mm SLRs.

Disadvantages

Except for the Pentax 67, which is configured like a giant 35mm SLR, has a rapid wind lever, and is generally fitted with a pentaprism finder, medium format SLRs are not ideal choices for action or sports photography. They’re great for portraiture, still life, nature, interiors, architecture, etc.—anything that is enhanced by a slow deliberate approach. Many medium format SLRs, especially those with focal-plane shutters are loud, and having a large, high-mass flipping mirror compromises their ability to capture sharp images handheld at slow shutter speeds (which is why I always shoot at least 2 frames of any given subject when using my Bronica S or EC at 1/30 sec!) Also, no matter the brand, medium format SLRs are complicated beasts that are more likely to break, and typically require more frequent (and more costly!) service than any comparable 35mm SLR. Like all SLRs, medium format models have a longer shutter release lag time than non-reflex cameras.

Recommended medium format SLRs

As with any camera, the choice here is largely subjective. It is possible to capture images of superlative quality with any medium format SLR, so handling, price, lens selection, reliability and even brand image are all valid criteria. I have personally shot with all the camera listed below unless otherwise noted, so while my impressions inevitably include some subjective elements, they have the advantage of being based on considerable hands-on experience.

Bronicas

My favorite Bronicas are the Bronica S of 1961, a simplified version of the original ultra-posh Bronica Z of 1959 and Bronica DeLuxe of c.1960, both of which were gorgeous, delicate, and unreliable masterpieces. My Bronica S focuses to about 18 inches with the 75mm f/2.8 Nikkor-P normal lens by extending the focusing tube (!), winds to the first frame in a mind-numbing 4-1/4 turns of the coaxial film wind crank, and fires with a “ker-clunk” that can wake the dead. This model has a reputation for unreliability but mine has functioned flawlessly for 8 years, has a nice contrasty original focusing screen, and can capture exquisitely sharp pictures. I also happily shoot with a Bronica EC with an electronically controlled focal plane shutter powered by a 6v PX-28 battery and an all-mechanical Bronica S2A, both of which have conventional helicoid focusing lenses that get down to about 0.5m and deliver impressive results. For the record the 75mm f/2.8 Nikkor-P.C. for Bronica has somewhat higher contrast than the Nikkor-P, the 6-element, 4-group 75mm f/2.8 Nikkor-H.C is the sharpest normal lens I’ve ever used on a Bronica. The hot ticket among Bronica lenses is reputed to be the Zenzanon MC 80mm f2.8 Lens marked Carl Zeiss JENA DDR but I’ve never shot with one. The 6x4.5cm-format, leaf shutter Bronica ETR, ETR-S and ETRSi have attracted a devoted following, and I’m happy with my leaf shutter 6x6 cm format Bronica SQ-A so far (except for the fact that that its 80mm f/2,8 Zenzanon lens only focuses down to 0.8m), but I’ve only run 2 rolls though it.

Bronica S of 1961, a simplified version of the original Bronica Z and D, has coaxial focusing knob and film wind crank. I love mine (see text).

Bronica EC of 1972 was the first medium format SLR with an electronically controlled focal plane shutter. It's hefty, but a great shooter.

Mamiya

In the past I’ve shot extensively with the Mamiya RB-67, a reliable but ponderous tank with a revolving back and close focusing via a bellows, and the lighter, handier Mamiya RZ-67, a modernized version with electronically controlled shutter. If you can live with the size and weight, they’re both great cameras and the lenses are excellent. I can also heartily recommend the Mamiya M645 1000S, a 6 x4.5cm SLR moist often seen sporting] a metering pentaprism and trigger grip but lacking interchangeable film backs. It too has excellent lenses except (sadly) for the 80mm f/1.9 Mamiya-Sekor, which is a real dog. The Later Mamiya 645 Pro and 645 Super have more advanced features including (at last) interchangeable film backs, hybrid metal/plastic body construction and plenty of positive hands-on reviews but I’ve never shot with either one.

Mamiya RB 67 Pro of 1970 is basically an updated Graflex with auto-diaphragm lenses and a revolving back. Ponderous, but a great shooter.

Pentacon Six (or 6)

Built in East Germany by the VEB Pentacon consortium and based on traditional Dresden camera designs, these idiosyncratic cameras have gobs of character and great Zeiss Jena lenses, but mediocre reliability, especially with respect to the film transport and frame positioning mechanisms, and the frame counter, which can be erratic. They have swing backs, so lack film magazines, but they do provide reasonably bright, contrasty viewing screens, and have a commendably quiet, low vibration shutter/mirror release action, which is partially attributable to their lack of instant return mirrors. Pentacon Sixes (and meter prism compatible Six TL's) are an acquired taste, but they’re capable of first-class results, and fair warning, they’re addictive. But before you take the plunge make sure you’re on friendly terms with an experienced repairman. Avoid earlier models badged Praktsix, which are even less reliable! Recommended lenses: 80mm f/2.8 Carl Zeiss Jena Biometar MC (multicoated) and 120mm f/2.8 Carl Zeiss Jena Biometar DDR.

Pentacon Six TL of late '60s was labeled TL because it accepts a meter prism. Idiosyncratic with a great lens line it's no paragon of reliability.

Kowa Six and Super 66

These are serviceable leaf shutter 6 x 6cm SLRs with a good lens line—Kowa always made good lenses. The less expensive Kowa Six has a hinged back and must be reloaded after each roll; the Super 66 uses odd L-shaped magazines that work well and commands higher prices. A full line of lenses and accessories was offered, but Kowas are most often found with waist-level finders. Overall quality of construction is decent and these cameras are reasonably reliable but hard to get fixed if they act up, Overall, a reasonably priced alternative for those getting into medium format SLRs.

Kowa Six MM. An upgraded Kowa Six with mirror lock and multi-exposure capability, it has a hinged back and must be reloaded after each roll.

Kowa Super 66 of c.1968 added unique L-shaped film magazines to the mix to make it more competitive. They work well, but sales were so-so.

Pentax 67 and 67II

Configured like a Texas-sized Nikon F and most often found sporting an interchangeable non-metered pentaprism and 105mm f/2.4 Takuma normal lens, the Pentax 67 is a beast, but it’s solid, beautifully made and performs very well thanks to a superb lens line. Introduced in 1969 and discontinued in as the very similar Pentax 67II (with beautiful ergonomic grip) in 2009, it lacks interchangeable film magazines, but the system offered a wide range of prime and zoom lenses, TTL pentaprism finders and other accessories. If the concept appeals to you, check it out before you pull the trigger. It’s a very good camera but its distinctive personality is not for everybody.

Pentax 67 with TTL meter rism, 105mm f/2.4 Takumar lens, wooden handgrip. It'a a tank all right, but also a superb vintage picture taker.

Pentax 645

The Pentax 645, introduced in 1984, is a 6 x 4.5 cm-format SLR with a built-in 1.5 fps motor drive, center-weighted TTL metering, multiple autoexposure modes, and a small LCD screen on the top plate that shows mode, exposure compensation, and frame count. It does not have interchangeable film backs; the film is loaded into holders that can’t be removed in mid-roll. I have had no hands-on experience with this camera, which was available inn several analog versions, but word of mouth is very positive, so check it out if it appeals to you.

Hasselblad:

A professional mainstay in its day, the Hasselblad 500 C/M is a classic all mechanical leaf shutter 6 x 6 cm SLR is beautifully made and finished and complemented by an extensive line of superb (and expensive!) Zeiss lenses. My limited experience with this camera was very positive despite the clunky system of early film magazines (later improved) that must be in sync with the camera to avoid blank exposures.

The Hasselblad 503CW is an upgraded version compatible with a motorized Winder CW and featuring TTL/OTF flash metering (with SCA390 or SCA 590 adapters) and an improved Hasselblad Acute-Matte D focusing screen. With the Hasselblad 2000FC of 1977 the company finally succeeded in producing a reliable focal plane shutter model with a titanium shutter that provided a top speed of 1/2000 sec, a larger non-vignetting mirror, and full compatibility with leaf shutter C and CF lenses and F-series shutterless lenses. The concept was further refined in the Hasselblad 205TCC of 1991, the 203FE of 1994, and the 2032FA of 1998. Any analog Hasselblad is capable of topnotch results, but the cameras and lenses generally command premium prices.

Hasselblad 503CW with 80mm f/2.8 Planar. An upgraded 500C/M with accessory motor drive and OTF TTL auotoflash via SCA adapters.

Hasselblad 2000FC with 80mm f/2.8 Zeiss Planar lens and PME TTL meter prism. Its titanium focal plane shutter tops out at 1/2000 sec., it takes C and CF leaf shutter lenses and F-series shutterless lenses. It's an awesome camera and a great shooter if you've got deep pockets.

Contax 645 AF:

The Contax 645 AF is a 6×4.5cm autofocus film camera, introduced by Kyocera under the Contax brand in 1999 as the heart if a premier professional camera, and it was discontinued in 2005. It features an electronically controlled vertical focal plane shutter with speeds to 1/4000 sec plus B, flash sync at up to 1/125 sec, manual, aperture priority or shutter priority metering, TTL auto-flash, spot, center-weighted, and averaging meter patterns, and an 80mm f/2 Carl Zeiss Planar normal lens. Regrettably I never had the chance to shoot with one if these gems, but the Contax 645 is reputed to be one of the best medium format cameras ever made and currently commands impressively high prices on the used market. Based on widespread positive reviews, I’m sure it’s a fine machine if you value exclusivity as well as performance and can afford what has clearly become a cult classic.

Contax 645 AF of 1999 is an analog AF SLR with TTL AE, shutter speeds to 1/4000 sec. etc., but it arrived at the cusp of the digital revolution.

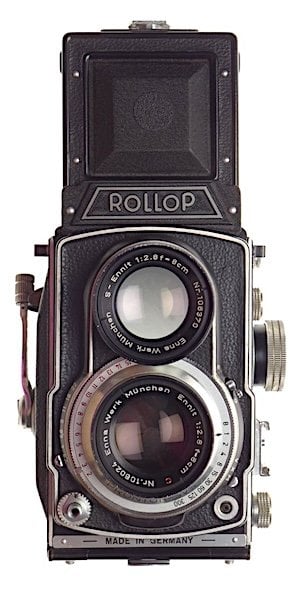

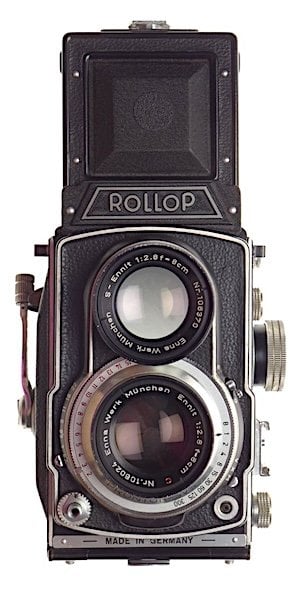

Twin-lens reflexes (TLRs)

The first roll-film TLR was the original Rolleiflex of 1929 and the breed reached the height if its popularity in the mid ‘50s. Though TLRs were made in a variety of formats, we’ll confine our discussion to the dominant form, 6x6 cm square-format cameras that take 120 roll film. All those we’ll cover have in-lens leaf shutters and waist-level viewfinders—top-mounted pentaprisms were available as accessories, but they were clunky and never very popular. Almost all the TLRs on this list have non-interchangeable lenses, the sole exception being the Mamyaflexes, later dubbed Mamiya TLRs, the only brand of interchangeable lens TLRs that made a serious impact on the marketplace. TLRs still have a certain old-timey charm, the best ones can capture mages of surpassing quality, and some really good ones are available at surprisingly modest prices.

Advantages:

Twin lens reflexes are, with the notable exceptions of Mamiya TLRs and the hefty Ansco Automatic Reflex, quite compact and lightweight for their format size. Their stationary reflex mirrors behind the (top) viewing lens provide a bright viewing and focusing image at wide open aperture before, during, and after the exposure with no momentary blackout, and do not cause any camera shake. Their leaf shutters are very quiet, most provide full flash sync at all shutter speeds, and the combination of good weight distribution and low vibration enables sharp handheld pictures to be shot at slow shutter speeds, down to about 1/15 sec.

Disadvantages:

Twin-lens reflexes have inherent parallax error due to the vertical distance between the viewing and taking lenses, and the effect of the error increases the closer you focus. All but Mamiyas (and the ancient French Rex Reflex, the exotic Koni-Omegaflex and the rare Zeiss twin-lens Contaflex of the ‘30s) have non-interchangeable lenses, which limits their optical flexibility, or interchangeable film backs. Rollei did offer high quality Mutar over-the-lens moderate wide-angle and telephoto attachments, but they’re large, heavy, expensive, and still don’t perform as well as prime lenses.

Rolleiflex

Few would argue that the Rolleiflex, made by Franke & Heidecke of Braunschweig, Germany is the greatest twin-lens reflex of all time. Practically any Rolleiflex of any vintage that takes 120 film is a great vintage shooter (the original Rolleflex of 1929 took 117 rolls, basically 120 on a narrower spool). However, the most useable ones are those with coated lenses, which date from the late ‘40s on up. The Rolleiflex Automat MX from the early ‘50s or the MX EVS from the mid ‘50s are stellar classics and their 75mm f/3,5 Zeiss Tessar or Schneider Xenar lenses are outstanding, except off axis at f/3.5-f/4 where they’re both somewhat soft. Later models like the Rolleiflex C, D, E, and F with 75mm f/3.5 or 80mm f/2.8 Zeiss Planar or Schneider Xenotar lenses are even better optically, but the practical performance difference is minuscule, and the earlier models are more affordable. The very last Rolleiflexes like the Aurum in gold, are gorgeous but stratospherically priced collectibles. All Rolleiflexes hold their value remarkably well so don’t expect to snag one for a song. All postwar (and some prewar) Rolleflexes provide effective parallax compensation over the entire focusing range using an ingenious moving frame under the viewing screen, all have automatic first frame positioning, and all accept Rolleinar close-up lens sets (in sizes I and II depending on the lens diameter) that provide parallax compensation at close focusing distances—the Rolleinar 1 and 2 are the post useful for shooting headshots and small object. Neither the built-in parallax compensation nor the Rolleinars provide the framing accuracy of an SLR, but they’re good enough for most practical purposes.

Rolleiflex Automat MX EVS of mid to late '50s with 75mm f/3.5 Tessar lens is a timeless classic and a phenomenal vintage picture taker.

Rolleiflex 2.8F with 80mm f/2.8 Planar lens of 1960 was made for 20 years with minor changes. A Rollei lover's prize it's great ,but expensive!

Rolleicord

Rolleiflex makers Franke & Heidecke began rolling out this simpler, less expensive line of TLRs back in 1933 to serve the needs of photo enthusiasts who wanted a good quality Rollei TLR at lower cost. Earlier models had 3-element Zeiss Triotar lenses but beginning with the Rollecord III of 1950, Rollecords were fitted with 4-element, 3-group 75mm f/3.5 Schneider Xenar lenses, as were some Rolleiflexes. The Rolliecord IV of 1953 added parallax compensation and interchangeable finder screens, and the Rolleicord Vb of 1962-1966 added an interchangeable finder loupe to the mix. No Rollecord ever had automatic first frame positioning, crank advance, combined film wind and shutter cocking, or a lens faster than f/3.5 thus maintaining its “amateur” status. But any Rolleicord with a coated Xenar lens is solidly made, beautifully finished and an excellent picture taker--a fine choice at a more reasonable cost for vintage film shooters.

Rolleicord Vb has parallax compensation, interchangeable finder screens, and a fine 75mm f/3.5 Xenar lens--a great unsung vintage shooter!

Ikoflex

The Zeiss Ikon Ikoflexes are good, solid cameras, and any postwar model with a coated 75mm f/3.5 Tessar is an excellent vintage shooter, especially the Ikoflex IIa and the top-of-the-line Ikioflex Favorit, which has a built-in uncoupled selenium meter and LVS settings. In general Ikoflexes are not as reliable as Rolleiflexes and they lack such refinements as crank wind, automatic, parallax compensation, and auto first frame positioning. However, Ikoflexes are distinctively beautiful and Zeiss did offer parallax-compensating close-up lenses which work very well.

Zeiss Ikoflex Favorit of 1957 to 1960. The last and best of the Ikoflex TLRs, it had a built-in uncoupled selenium meter at top (shown covered).

Mamiyaflex and Mamiya TLRs

Although these interchangeable-lens TLRs are ponderous and their form factor is, um, inelegant, they are supremely functional, very flexible, and provide extremely close focusing (albeit with red parallax indication marks rather than parallax compensation) and all require manual first frame positioning. The original Mamyaflex C (1956) and C2 (1958) are heavier than later models and have separate film wind and shutter cocking functions. However the early single-coated 80mm f/2.8 Mamiya-Sekor lens (a 5-element, 3-group Heliar formula) in Seikosha MX 1-1/400 sec shutter has an 11-bladed diaphragms that enhances its smooth transitions and gorgeous bokeh. Later models like the C220 and C330 (all sub-groups) are lighter, feature crank wind, and have double and blank exposure prevention. Except for the 135mm f/4.5 lens set, which is mediocre, all the lens units (which consist of a viewing and a taking lens, the latter in a shutter) are outstanding, and the range was expanded from 65mm to 180mm on the C/C2 to 55 to 250mm on the C330. The lens units are, heavy and bulky, and switching them is a slow, fiddly procedure, but the ability to change lenses is well worth the trouble and is the signature feature of Mamiya TLRs. I find them all to be lovable clunkers, and you can’t argue with the on-film results, which are outstanding. If you want to experience the atavistic joy of shooting with one if these beasts, try the original Mamiyaflex C (the one with the little pointy feet on the base) or the C2 which is the same camera with a flat bottom. Just make sure to wind to the next exposure as soon as you take the shot, and to cock the shutter just before you take the next shot, and you’ll do just fine. Mamiya TLRs aren’t for everybody, but they offer a reasonably priced route into vintage medium format.

Mamiyaflex C of 1956, here with 105rmm f/3.5 lens set, was the first interchangeable lens Mamiya TLR. Note funny pointy "feet" on the base.

Mamiya C330f of 1972, the penultimate Mamiya TLR, had a focus lock lever, many other refinements, was much lighter than the C or the C2.

Other good choices in widely available TLRs

Yashica-Mat (all types): These very popular vintage Japanese TLRs feature 80mm f/3..5 Yahinon lenses (very good quality Tessars), crank wind, and Riolleiflex-inspired styling.

Minolta Autocord: Rolleicord inspired styling, crank wind single bottom lever focusing, and excellent Tessar-type 75mm f/3.5 Rokkor lenses. They tend to be higher priced than Yashica-Mats and other Japanese TLRs.

Ricoh Diacord: Knob wind, signature “see-saw” focusing levers, and excellent 80mm fl3.5 Rukenin lens, a bice Tessar type. The Diacord L has a built-in integrated selenium meter, Avoid the Ricohmatic 225 which has excellent specs but questionable reliability.

Kalloflex: Less common, with superb 75mm f/3.5 Prominar lens (a Tessar type) and signature right-hand coaxial film wind crank and focusing knob. They tend to be pricey, but you’ll have the only one on the block!

Ciroflex F: All Ciroflexes are American made (in Delaware, Ohio) mechanically primitive TLRs with red window film advance, snail cam focusing mechanism, and separate shutter cocking, but all are decent picture takers and widely available at bargain basement prices—except for the Model F, which is the one to have! The highest-spec Ciro-flex, the F paired an excellent 83mm f/3.2, four-element Wollensak Raptar lens and a Rapax 1-1/400 sec. Full Sync shutter and can give a Rollei a run for the money in pure picture taking ability despite its other low-end specs. It’s the only vintage U.S.-made TLR I can recommend without reservation, but it’s hard to find and on the pricey side at $200-$250.

Sadly I cannot recommend the Kodak Reflex (either model), which takes 620 film, despite its good lens, nor the glorious Ansco Automatic Reflex, the most advanced TLR ever made in the U.S.A. because of its mediocre reliability and (decent but unspectacular) 3-element lens, a concession to the bean counters when they realized how much it cost to produce the rest if the canera, especially it ultra-high-tech focusing system.

Nikon F2 of 1971 to 1980 is reputed to be the best 35mm SLR Nikon ever made. It's shown here with DP-1 prism and 50mm f/1.4 Nikkor.

Advantages

]The big advantage of any SLR is its ability to provide parallax-free viewing with virtually any lens that can be mounted in the camera, and at any focusing distance down to, and including, the macro range. This advantage is optimized in 35mm SLRs, which will accommodate lenses ranging from fisheyes to super-telephotos. Some pro-grade 35mm SLRs, notably the Nikon F and F2, original Canon F-1, and Minolta XK have viewfinders that show 100% of the on-film image, but most show about 97% which is close enough for most applications. Most 35mm SLRs (e.g. the Nikon F) provide a viewfinder magnification of about 0.8x (80% of life-size) with the 50mm normal lens. That’s why some 35mm SLRs from major makers, notably Exakta, Nikon, Minolta, and Topcon fitted their cameras with 58mm lenses to achieve a life-size (1:1) viewing image, and Olympus configured their OM-series viewfinders to achieve a 0.92x magnification with a coverage of 97%. Optical flexibility is the SLR’s sine qua non and is largely responsible for the 35mm SLR’s dominance from the mid ‘60s until the dawn of the digital era around 2002.

Canton F-1 NEW, the final and most advanced iteration of the F-1, debuted in 1981. it features a titanium shutter with speeds to 1/2000 sec.

Disadvantages

The major downsides of 35mm SLRs are all direct results of the moving mirror required for through-the-lens viewing and the relatively bulky mechanical assembly comprising the mirror box. Since the mirror must move out if the light path before the shutter fires its movement causes some degree of camera shake that affects the exposure and cannot be eliminated entirely even with ingenious braking systems, etc. Fortunately, the action of the returning mirror takes place after the shutter fires, so it has no effect on the captured image. Result: shooting handheld at slow shutter speeds with a 35mm SLR is more likely to result in unsharp pictures, especially when shooting at 1/30 sec and slower. Also, the combined sound of an SLR’s shutter and mirror is usually noticeably louder that the discreet click of a typical rangefinder camera, and SLRs are usually larger and heavier than comparable rangefinder cameras due to the extra size and weight of the mirror box and pentaprism. Indeed, it was the quest for smaller sized SLRs that resulted in the “compact SLR revolution” of the ‘70s that yielded such diminutive classics as the Olympus OM series and the Pentax ME and MX. Finally, SLRs generally have a longer shutter release time lag—the interval between pressing the shutter release and executing the exposure—than cameras without reflex mirrors. Many of the factors noted above also explain why mirrorless cameras have largely supplanted DSLRs in the current digital era.

Toopcon Super D (marketed in the U.S. by Beseler) had one if the first TTL metering systems. Lens is the superb 58mm f/1.4 R.E. Auto-Topcor.

Recommended 35mm SLRs

There are literally scores of worthy 35mm SLRs currently available on the used market and it’s impossible to list them all here. However, here is a selection of my personal favorites, all of which have been vetted with experienced camera repair people and longtime camera experts. For the convenience of vintage analog shooters, they’re arranged in 3 broad categories, pro-aimed, enthusiast or intermediate level, and broad spectrum of mass market. Note: Just because a camera is listed in one group doesn’t mean its use is confined to that category, a notable example being the “Intermediate” Nikon FM2, which was the mainstay of countless pros.

Canon T90 of 1986, the top of T-series line, is a unique multi-mode FD-mount SLR with a built-in 4.5 fps motor. It's a great vintage shooter.

Pro-level 35mm SLRs

The following are all superbly constructed, super-rugged, full featured system cameras with extensive lines of first-rate optics that were marketed as professional cameras and/or used by many pros. The Nikon F (all iterations, now available at surprisingly modest prices), the Nikon F2 (widely regarded as Nikon’s best 35mm SLR ever), the Canon F-1 and the mildly upgraded F-1n, both extremely robust and reliable, the Canon New F-1, Canon’s top-of-the-line model from 1981 to 1992, and the Canon T90 of 1986 a unique multi-mode FD-mount SLR with built-in 4.5 fps motor drive, three metering systems, eight auto-exposure modes and two manual exposure modes for maximum versatility. The Topcon RE Super of 1963, marketed as a pro camera and used by the U.S. Navy, features an ingenious CdS-cell metering system behind slits in the reflex mirror, which reduces finder brightness somewhat, and its body as not quite as tanklike as a Nikon F2 or Canon F-1, but its line of Topcor lenses equals or surpasses that of its competitors. Some experts believe that the Leica R6.2 merits inclusion in this category due to its excellent (and expensive!) lens line and its straightforward design and robust reliability, which appealed to pros. Other late models worth looking into: Canon EOS 1-V, and the late lamented top-of-the line Nikon F6.

Intermediate level 35mm SLRs

The following cameras are in widespread use by serious photographers and some pros, have stood the test of time, and are often available at very moderate prices: Pentax Spotmatic, and the compact K-mount MX, Minolta SR-T 102/303, Nikon FM, FM2, FM3a (limited production, coveted, and expensive) and FE, Canon FTb, EF, and A1, Olympus OM-1, OM-1n OM-2n, Yashica FX-103 Program, Minolta X700, the Nikkormat FTn, and the Nikon F3/F3HP a pro/enthusiast crossover.

Budget-priced, mass market 35mm SLRs

Pentax K1000 (the archetypical student SLR), Canon AE-1 (over 5 million sold!), Canon TLb, Nikon EM, Konica Autoreflex TC, Chinon CP-7m, Olympus OMG. There are countless others available used at bargain prices.

Medium format SLRs (6x4.5, 6x6 and 6x7cm)

The main reason to choose a medium format SLR boils down to a single two-word phrase: image quality. If you’re determined to capture images for the ages on film, often make enlargements of 16 x 20 inches and larger, are prepared to tote a heavier, slower operating camera, pay more for a clean functional body (and considerably more for extra lenses) and shell out more for film, processing, and hi-res scanning, maybe a medium format SLR is the camera for you. These are great cameras, but they require a slower, more deliberate approach if you expect to get the most out of them. All take readily available 120 roll film, and (depending on the format) provide 16, 12, or 10 exposures per roll. Most have interchangeable film backs, a good thing since loading roll film is hardly the last word in speed or convenience. All have interchangeable lenses and detachable finders, and most have user-interchangeable finder screens.

Advantages

All medium format SLRs provide parallax-free viewing and though-the-lens focusing with all compatible lenses, and most show close to 100% of the on-film image, laterally reversed, when using a waist-level finder; often somewhat less than 100% if you mount a pentaprism finder. Many focal plane shutter models provide close focusing down to 0.5 or so with the normal lens, but others (e.g. the Hasselblad 500C and C/M) have a leaf shutter in each lens and minimum focus distance of 0.9m (3 ft.) with the normal lens. The latter require close-up lenses or accessories to get closer. All medium format SLRs provide automatic film stop and frame counting once you manually position the film before winding to the first exposure, but on some models it’s possible to get a blank exposure if the film back is out of sync with the shutter cocking mechanism in the body. In general, medium format SLRs have good handing and ergonomics, but they’re a lot larger and heavier than all but the heftiest pro 35mm SLRs.

Disadvantages

Except for the Pentax 67, which is configured like a giant 35mm SLR, has a rapid wind lever, and is generally fitted with a pentaprism finder, medium format SLRs are not ideal choices for action or sports photography. They’re great for portraiture, still life, nature, interiors, architecture, etc.—anything that is enhanced by a slow deliberate approach. Many medium format SLRs, especially those with focal-plane shutters are loud, and having a large, high-mass flipping mirror compromises their ability to capture sharp images handheld at slow shutter speeds (which is why I always shoot at least 2 frames of any given subject when using my Bronica S or EC at 1/30 sec!) Also, no matter the brand, medium format SLRs are complicated beasts that are more likely to break, and typically require more frequent (and more costly!) service than any comparable 35mm SLR. Like all SLRs, medium format models have a longer shutter release lag time than non-reflex cameras.

Recommended medium format SLRs

As with any camera, the choice here is largely subjective. It is possible to capture images of superlative quality with any medium format SLR, so handling, price, lens selection, reliability and even brand image are all valid criteria. I have personally shot with all the camera listed below unless otherwise noted, so while my impressions inevitably include some subjective elements, they have the advantage of being based on considerable hands-on experience.

Bronicas

My favorite Bronicas are the Bronica S of 1961, a simplified version of the original ultra-posh Bronica Z of 1959 and Bronica DeLuxe of c.1960, both of which were gorgeous, delicate, and unreliable masterpieces. My Bronica S focuses to about 18 inches with the 75mm f/2.8 Nikkor-P normal lens by extending the focusing tube (!), winds to the first frame in a mind-numbing 4-1/4 turns of the coaxial film wind crank, and fires with a “ker-clunk” that can wake the dead. This model has a reputation for unreliability but mine has functioned flawlessly for 8 years, has a nice contrasty original focusing screen, and can capture exquisitely sharp pictures. I also happily shoot with a Bronica EC with an electronically controlled focal plane shutter powered by a 6v PX-28 battery and an all-mechanical Bronica S2A, both of which have conventional helicoid focusing lenses that get down to about 0.5m and deliver impressive results. For the record the 75mm f/2.8 Nikkor-P.C. for Bronica has somewhat higher contrast than the Nikkor-P, the 6-element, 4-group 75mm f/2.8 Nikkor-H.C is the sharpest normal lens I’ve ever used on a Bronica. The hot ticket among Bronica lenses is reputed to be the Zenzanon MC 80mm f2.8 Lens marked Carl Zeiss JENA DDR but I’ve never shot with one. The 6x4.5cm-format, leaf shutter Bronica ETR, ETR-S and ETRSi have attracted a devoted following, and I’m happy with my leaf shutter 6x6 cm format Bronica SQ-A so far (except for the fact that that its 80mm f/2,8 Zenzanon lens only focuses down to 0.8m), but I’ve only run 2 rolls though it.

Bronica S of 1961, a simplified version of the original Bronica Z and D, has coaxial focusing knob and film wind crank. I love mine (see text).

Bronica EC of 1972 was the first medium format SLR with an electronically controlled focal plane shutter. It's hefty, but a great shooter.

Mamiya

In the past I’ve shot extensively with the Mamiya RB-67, a reliable but ponderous tank with a revolving back and close focusing via a bellows, and the lighter, handier Mamiya RZ-67, a modernized version with electronically controlled shutter. If you can live with the size and weight, they’re both great cameras and the lenses are excellent. I can also heartily recommend the Mamiya M645 1000S, a 6 x4.5cm SLR moist often seen sporting] a metering pentaprism and trigger grip but lacking interchangeable film backs. It too has excellent lenses except (sadly) for the 80mm f/1.9 Mamiya-Sekor, which is a real dog. The Later Mamiya 645 Pro and 645 Super have more advanced features including (at last) interchangeable film backs, hybrid metal/plastic body construction and plenty of positive hands-on reviews but I’ve never shot with either one.

Mamiya RB 67 Pro of 1970 is basically an updated Graflex with auto-diaphragm lenses and a revolving back. Ponderous, but a great shooter.

Pentacon Six (or 6)

Built in East Germany by the VEB Pentacon consortium and based on traditional Dresden camera designs, these idiosyncratic cameras have gobs of character and great Zeiss Jena lenses, but mediocre reliability, especially with respect to the film transport and frame positioning mechanisms, and the frame counter, which can be erratic. They have swing backs, so lack film magazines, but they do provide reasonably bright, contrasty viewing screens, and have a commendably quiet, low vibration shutter/mirror release action, which is partially attributable to their lack of instant return mirrors. Pentacon Sixes (and meter prism compatible Six TL's) are an acquired taste, but they’re capable of first-class results, and fair warning, they’re addictive. But before you take the plunge make sure you’re on friendly terms with an experienced repairman. Avoid earlier models badged Praktsix, which are even less reliable! Recommended lenses: 80mm f/2.8 Carl Zeiss Jena Biometar MC (multicoated) and 120mm f/2.8 Carl Zeiss Jena Biometar DDR.

Pentacon Six TL of late '60s was labeled TL because it accepts a meter prism. Idiosyncratic with a great lens line it's no paragon of reliability.

Kowa Six and Super 66

These are serviceable leaf shutter 6 x 6cm SLRs with a good lens line—Kowa always made good lenses. The less expensive Kowa Six has a hinged back and must be reloaded after each roll; the Super 66 uses odd L-shaped magazines that work well and commands higher prices. A full line of lenses and accessories was offered, but Kowas are most often found with waist-level finders. Overall quality of construction is decent and these cameras are reasonably reliable but hard to get fixed if they act up, Overall, a reasonably priced alternative for those getting into medium format SLRs.

Kowa Six MM. An upgraded Kowa Six with mirror lock and multi-exposure capability, it has a hinged back and must be reloaded after each roll.

Kowa Super 66 of c.1968 added unique L-shaped film magazines to the mix to make it more competitive. They work well, but sales were so-so.

Pentax 67 and 67II

Configured like a Texas-sized Nikon F and most often found sporting an interchangeable non-metered pentaprism and 105mm f/2.4 Takuma normal lens, the Pentax 67 is a beast, but it’s solid, beautifully made and performs very well thanks to a superb lens line. Introduced in 1969 and discontinued in as the very similar Pentax 67II (with beautiful ergonomic grip) in 2009, it lacks interchangeable film magazines, but the system offered a wide range of prime and zoom lenses, TTL pentaprism finders and other accessories. If the concept appeals to you, check it out before you pull the trigger. It’s a very good camera but its distinctive personality is not for everybody.

Pentax 67 with TTL meter rism, 105mm f/2.4 Takumar lens, wooden handgrip. It'a a tank all right, but also a superb vintage picture taker.

Pentax 645

The Pentax 645, introduced in 1984, is a 6 x 4.5 cm-format SLR with a built-in 1.5 fps motor drive, center-weighted TTL metering, multiple autoexposure modes, and a small LCD screen on the top plate that shows mode, exposure compensation, and frame count. It does not have interchangeable film backs; the film is loaded into holders that can’t be removed in mid-roll. I have had no hands-on experience with this camera, which was available inn several analog versions, but word of mouth is very positive, so check it out if it appeals to you.

Hasselblad:

A professional mainstay in its day, the Hasselblad 500 C/M is a classic all mechanical leaf shutter 6 x 6 cm SLR is beautifully made and finished and complemented by an extensive line of superb (and expensive!) Zeiss lenses. My limited experience with this camera was very positive despite the clunky system of early film magazines (later improved) that must be in sync with the camera to avoid blank exposures.

The Hasselblad 503CW is an upgraded version compatible with a motorized Winder CW and featuring TTL/OTF flash metering (with SCA390 or SCA 590 adapters) and an improved Hasselblad Acute-Matte D focusing screen. With the Hasselblad 2000FC of 1977 the company finally succeeded in producing a reliable focal plane shutter model with a titanium shutter that provided a top speed of 1/2000 sec, a larger non-vignetting mirror, and full compatibility with leaf shutter C and CF lenses and F-series shutterless lenses. The concept was further refined in the Hasselblad 205TCC of 1991, the 203FE of 1994, and the 2032FA of 1998. Any analog Hasselblad is capable of topnotch results, but the cameras and lenses generally command premium prices.

Hasselblad 503CW with 80mm f/2.8 Planar. An upgraded 500C/M with accessory motor drive and OTF TTL auotoflash via SCA adapters.

Hasselblad 2000FC with 80mm f/2.8 Zeiss Planar lens and PME TTL meter prism. Its titanium focal plane shutter tops out at 1/2000 sec., it takes C and CF leaf shutter lenses and F-series shutterless lenses. It's an awesome camera and a great shooter if you've got deep pockets.

Contax 645 AF:

The Contax 645 AF is a 6×4.5cm autofocus film camera, introduced by Kyocera under the Contax brand in 1999 as the heart if a premier professional camera, and it was discontinued in 2005. It features an electronically controlled vertical focal plane shutter with speeds to 1/4000 sec plus B, flash sync at up to 1/125 sec, manual, aperture priority or shutter priority metering, TTL auto-flash, spot, center-weighted, and averaging meter patterns, and an 80mm f/2 Carl Zeiss Planar normal lens. Regrettably I never had the chance to shoot with one if these gems, but the Contax 645 is reputed to be one of the best medium format cameras ever made and currently commands impressively high prices on the used market. Based on widespread positive reviews, I’m sure it’s a fine machine if you value exclusivity as well as performance and can afford what has clearly become a cult classic.

Contax 645 AF of 1999 is an analog AF SLR with TTL AE, shutter speeds to 1/4000 sec. etc., but it arrived at the cusp of the digital revolution.

Twin-lens reflexes (TLRs)

The first roll-film TLR was the original Rolleiflex of 1929 and the breed reached the height if its popularity in the mid ‘50s. Though TLRs were made in a variety of formats, we’ll confine our discussion to the dominant form, 6x6 cm square-format cameras that take 120 roll film. All those we’ll cover have in-lens leaf shutters and waist-level viewfinders—top-mounted pentaprisms were available as accessories, but they were clunky and never very popular. Almost all the TLRs on this list have non-interchangeable lenses, the sole exception being the Mamyaflexes, later dubbed Mamiya TLRs, the only brand of interchangeable lens TLRs that made a serious impact on the marketplace. TLRs still have a certain old-timey charm, the best ones can capture mages of surpassing quality, and some really good ones are available at surprisingly modest prices.

Advantages:

Twin lens reflexes are, with the notable exceptions of Mamiya TLRs and the hefty Ansco Automatic Reflex, quite compact and lightweight for their format size. Their stationary reflex mirrors behind the (top) viewing lens provide a bright viewing and focusing image at wide open aperture before, during, and after the exposure with no momentary blackout, and do not cause any camera shake. Their leaf shutters are very quiet, most provide full flash sync at all shutter speeds, and the combination of good weight distribution and low vibration enables sharp handheld pictures to be shot at slow shutter speeds, down to about 1/15 sec.

Disadvantages:

Twin-lens reflexes have inherent parallax error due to the vertical distance between the viewing and taking lenses, and the effect of the error increases the closer you focus. All but Mamiyas (and the ancient French Rex Reflex, the exotic Koni-Omegaflex and the rare Zeiss twin-lens Contaflex of the ‘30s) have non-interchangeable lenses, which limits their optical flexibility, or interchangeable film backs. Rollei did offer high quality Mutar over-the-lens moderate wide-angle and telephoto attachments, but they’re large, heavy, expensive, and still don’t perform as well as prime lenses.

Rolleiflex

Few would argue that the Rolleiflex, made by Franke & Heidecke of Braunschweig, Germany is the greatest twin-lens reflex of all time. Practically any Rolleiflex of any vintage that takes 120 film is a great vintage shooter (the original Rolleflex of 1929 took 117 rolls, basically 120 on a narrower spool). However, the most useable ones are those with coated lenses, which date from the late ‘40s on up. The Rolleiflex Automat MX from the early ‘50s or the MX EVS from the mid ‘50s are stellar classics and their 75mm f/3,5 Zeiss Tessar or Schneider Xenar lenses are outstanding, except off axis at f/3.5-f/4 where they’re both somewhat soft. Later models like the Rolleiflex C, D, E, and F with 75mm f/3.5 or 80mm f/2.8 Zeiss Planar or Schneider Xenotar lenses are even better optically, but the practical performance difference is minuscule, and the earlier models are more affordable. The very last Rolleiflexes like the Aurum in gold, are gorgeous but stratospherically priced collectibles. All Rolleiflexes hold their value remarkably well so don’t expect to snag one for a song. All postwar (and some prewar) Rolleflexes provide effective parallax compensation over the entire focusing range using an ingenious moving frame under the viewing screen, all have automatic first frame positioning, and all accept Rolleinar close-up lens sets (in sizes I and II depending on the lens diameter) that provide parallax compensation at close focusing distances—the Rolleinar 1 and 2 are the post useful for shooting headshots and small object. Neither the built-in parallax compensation nor the Rolleinars provide the framing accuracy of an SLR, but they’re good enough for most practical purposes.

Rolleiflex Automat MX EVS of mid to late '50s with 75mm f/3.5 Tessar lens is a timeless classic and a phenomenal vintage picture taker.

Rolleiflex 2.8F with 80mm f/2.8 Planar lens of 1960 was made for 20 years with minor changes. A Rollei lover's prize it's great ,but expensive!

Rolleicord

Rolleiflex makers Franke & Heidecke began rolling out this simpler, less expensive line of TLRs back in 1933 to serve the needs of photo enthusiasts who wanted a good quality Rollei TLR at lower cost. Earlier models had 3-element Zeiss Triotar lenses but beginning with the Rollecord III of 1950, Rollecords were fitted with 4-element, 3-group 75mm f/3.5 Schneider Xenar lenses, as were some Rolleiflexes. The Rolliecord IV of 1953 added parallax compensation and interchangeable finder screens, and the Rolleicord Vb of 1962-1966 added an interchangeable finder loupe to the mix. No Rollecord ever had automatic first frame positioning, crank advance, combined film wind and shutter cocking, or a lens faster than f/3.5 thus maintaining its “amateur” status. But any Rolleicord with a coated Xenar lens is solidly made, beautifully finished and an excellent picture taker--a fine choice at a more reasonable cost for vintage film shooters.

Rolleicord Vb has parallax compensation, interchangeable finder screens, and a fine 75mm f/3.5 Xenar lens--a great unsung vintage shooter!

Ikoflex